This headline is a lie. It’s not that I think algorithms are bad. They’re not. Honestly, I think that’s how many of us move through our days without killing ourselves or someone else. We habitually take the medications prescribed by our doctors; we cook our eggs (and avoid salmonella); we follow the steps for safely backing our cars out of the driveway; we put on our socks before our shoes.

Even certain mathematical algorithms are very useful, like the order of operations (or PEMDAS).

But in the end, I think that dictated algorithms are not so great for people, especially people who are learning a new skill, and especially when the algorithm has little to no meaning or context.

Don’t know what an algorithm is? Check out my earlier post defining algorithms.

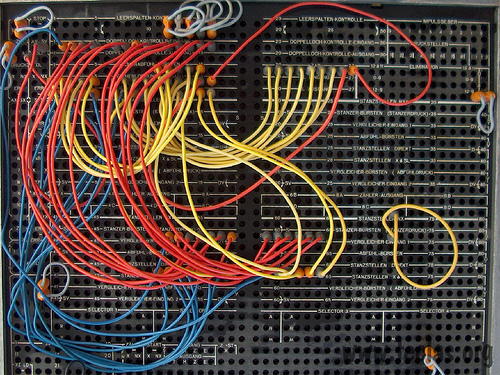

People Aren’t Machines

There are many different educational philosophies that drive how we teach math. For generations, teachers worked under the assumption that young minds were tabula rasas or blank slates. Some educators took this to mean that we were empty pitchers, waiting to be filled with information.

This is how teaching algorithms got such a strong-hold on our educational system. Teachers were expected to introduce material to students, who were seen as completely ignorant of any part of the process. Through instruction, students learned step-by-step processes, with very little context.

In recent years, however, our understanding of neurology and psychology has deepened. We understand, for example, that children’s personalities are somewhat set at birth. And that their brains develop in predictable ways. We are also beginning to realize that certain types of learning and teaching promote deeper understanding.

The result is a better sense of students as individuals. Instead of a class filled with homogeneous little minds, we know now that kids (and grownups) are wildly different–in the way they digest information and approach problems. (To be fair, this is closer to John Locke’s original theory of tabula rasa, in which he states that the purpose of education is to create intellect, not memorize facts.)

In terms of a moral, there’s not much I recommend in this Pink Floyd video, but I can certainly identify with the kids’ anger at being treated like cogs in the educational system. Besides, it’s cool.

A Case for Critical Thinking

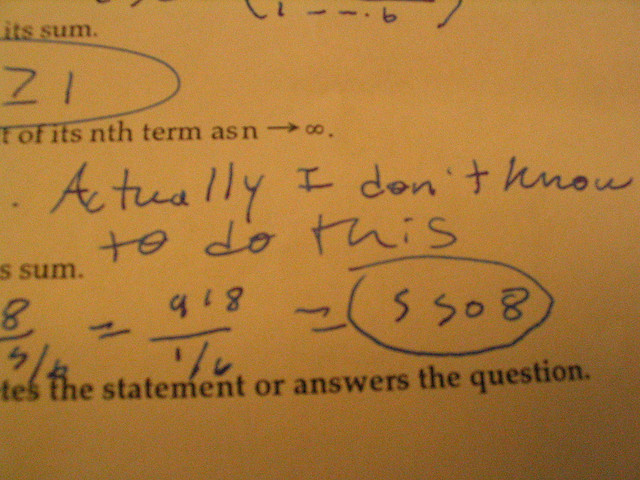

Certainly critical thinking is not completely absent in the teaching of algorithms. It’s marvelous when kids (and adults) make connections within the steps of a mathematical process. But critical thinking is much more likely, when the process is more open-ended. Give kids square tiles to help them understand quadratic equations, and they’ll likely start factoring without help. Let students play around with addition of multi-digit numbers, and they’ll start figuring out place value on their own.

You can’t beat that kind of learning.

See, when someone tells us something, our brains may or may not really engage. But when we’re already engaged in the discovery process, we’re much more likely to make big connections and remember them longer.

That’s not to say that learning algorithms is bad. But think of the way you might add two multi-digit numbers without a calculator. Instead of stacking them up and adding from right to left (remembering to carry), you might do something completely different, like add up all of the hundreds and tens and ones — and add again. In many ways, you’re still following the algorithm, but in a deconstructed way.

And in the end, who cares what process you follow–as long as you get to the correct answer and feel confident.

Teaching Algorithms is Easier, Sort Of

So if discovering processes is so much better, why does much of our educational system still teach algorithms? Well, because it’s more efficient in a lot of ways. It’s easier to stand in front of a group of kids and teach a step-by-step process. It’s harder–and noisier–to let kids work in groups, using manipulatives to answer open-ended questions. It might even take longer.

But I say that based on what we now know about kids’ personalities and brains, we’re not doing them much good with lecture-style classes. So in the long run, it’s easier to teach with discovery-based methods. Kids remember the information longer and get great neurological exercise. This allows for many more connections. At that point, the teacher is more of a coach than anything else.

In the end, we all use algorithms. But isn’t it better when we decide what steps to follow, through trial and error, a gut instinct or discovering the basic concepts underlying the process? That’s where we have a big edge over machines. After all, humans are inputting the algorithms that machines use.